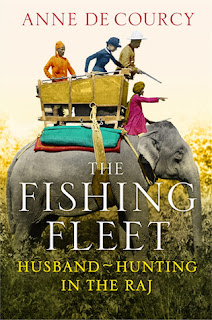

The Fishing Fleet: Husband-Hunting in the Raj

Summary (from the publisher): From the late 19th century, when the Raj was at its height, many of Britain's best and brightest young men went out to India to work as administrators, soldiers, and businessmen. With the advent of steam travel and the opening of the Suez Canal, countless young women, suffering at the lack of eligible men in Britain, followed in their wake. They were known as the Fishing Fleet, and this book is their story.

For these young women, often away from home for the first time, one thing they could be sure of was a rollicking good time. By the early twentieth century, a hectic social scene was in place, with dance parties, picnics, tennis tournaments and perhaps a tiger shoot and glittering dinner at a raja's palace thrown in. And, with men outnumbering women by roughly four to one, romances were conducted at alarming speed and marriages were frequent. But after the honeymoon life often changed dramatically: whisked off to remote outposts, they found it a far cry from the social whirlwind of their first arrival.

Anne de Courcy's sparkling narrative is enriched by a wealth of first-hand sources which bring this forgotten era vividly to life.

For these young women, often away from home for the first time, one thing they could be sure of was a rollicking good time. By the early twentieth century, a hectic social scene was in place, with dance parties, picnics, tennis tournaments and perhaps a tiger shoot and glittering dinner at a raja's palace thrown in. And, with men outnumbering women by roughly four to one, romances were conducted at alarming speed and marriages were frequent. But after the honeymoon life often changed dramatically: whisked off to remote outposts, they found it a far cry from the social whirlwind of their first arrival.

Anne de Courcy's sparkling narrative is enriched by a wealth of first-hand sources which bring this forgotten era vividly to life.

Review: I received an uncorrected proof copy of this book from HarperCollins.

During the Victorian period in Great Britain, "trade with India, the jewel in Britain's burgeoning commercial Empire, was vast and the promise of wealth and success - if they survived disease and peril - beckoned the young men of the Company" (1-2). Since union with Indian women was socially unacceptable by the mid-1800s, many British women followed the men to India in search of a successful spouse. These women, known as the Fishing Fleet, and their stories are detailed in this history. In a time when failing to marry meant social disgrace for young women, India was seen as a desirable marriage market, particularly since men greatly outnumbered women. Marriage was approached with speed and more as a business transaction than a romantic pursuit.

The importance of becoming successful in the eyes of the empire and society was emphasized by the fact that men who travelled to India were granted "no home leave for eight years" so "young men often left in the knowledge that they would never see someone dear to them again" (57). It seems unthinkable in today's world to commit to making a lengthy trip by ship to a inhospitable climate, where you would be stuck without respite for at least eight years. Knowing the difficulties and infrequency of traveling home, its little wonder that the Fishing Fleet came about. Otherwise these men would go years without encountering eligible British women they could marry.

Each chapter of this book is centered around a specific aspect of the Fishing Fleet, including the voyages, the parties, courtships, engagements, first homes, etc. De Courcy clearly spent a great deal of time researching unpublished memoirs, letters, photographs, and diaries to build a rich picture of life in India and includes copious real-life examples. Although I enjoyed the book immensely and appreciate the overarching history provided by the book, my favorite chapters were the few in which de Courcy focused on a particular individual. For example, one chapter is devoted to Elisabeth Bruce, the daughter of the Viceroy and her story of courtship and marriage in India. (In particular, I was amazed to learn that when Elisabeth married, she had a "700-lb wedding cake, for which 4,000 eggs had been used" (123)). This sort of case study chapter reeled me in more than the general chapters with endless examples pulled from the author's research.

In many ways, the British regime in India was their ceaseless attempt to replicate British society and culture in a vastly different climate and world. Most of Victorian dress was vastly unsuitable for the climate, but was worn nonetheless. For example, "one of the stranger habits of the Raj was the insistence on wearing flannel next to the skin, advocated by virtually all doctors until well into the twentieth century" (85). In some parts of India the temperature can exceed 120 degrees Fahrenheit in the shade, so its difficult to imagine wearing flannel underwear. In addition to the climate extremes and the diseases associated with India, it was still considered only proper for British children to attend British schools. Thus mothers were torn between sending their children off alone to boarding school in Great Britain and remaining with their husbands in India. "One after one the babies grow into companionable children; one after one England claims them, till the mother's heart and house are left unto her desolate" (308).

At times I almost felt as if chapters of this book were written in no particular order and then pieced together before publication. For example, it is repeated endlessly throughout the book that men were not encouraged to marry before the age of 30. This became such an oft-repeated sentence that I started to become really annoyed after having read it for at least the tenth time. However, perhaps the author felt the need to repeat this since she was unsure of which chapter would be read first, possibly leaving the readers without critical information that would only appear in later chapters. Additionally, I was disappointed that my advance copy lacked the many illustrations that the final copy will have.

This book is a social history of Britain's rule in India. Where other books about Britain's empire in India detail the politics, this deals with marriage and home life, which I found interesting. Beyond just the practice of shipping off ladies to India to marry, I learned a great deal about the social life, domestic practices, education, and lifestyles of Europeans in India during the 1800s.

Stars: 4

Comments

Post a Comment