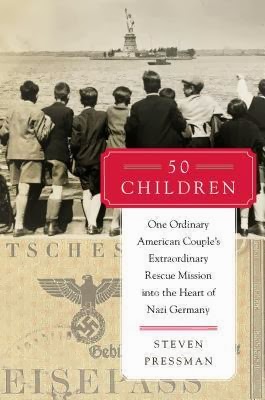

50 Children: One Ordinary American Couple's Extraordinary Rescue Mission into the Heart of Nazi Germany

Summary (from the publisher): Based on the acclaimed HBO documentary, the astonishing true story of how one American couple transported fifty Jewish children from Nazi-occupied Austria to America in 1939--the single largest group of unaccompanied refugee children allowed into the United States--for readers of In the Garden of Beasts and A Train in Winter.

In early 1939, America's rigid immigration laws made it virtually impossible for European Jews to seek safe haven in the United States. As deep-seated anti-Semitism and isolationism gripped much of the country, neither President Roosevelt nor Congress rallied to their aid.

Yet one brave Jewish couple from Philadelphia refused to silently stand by. Risking their own safety, Gilbert Kraus, a successful lawyer, and his stylish wife, Eleanor, traveled to Nazi-controlled Vienna and Berlin to save fifty Jewish children. Steven Pressman brought the Kraus's rescue mission to life in his acclaimed HBO documentary, 50 Children. In this book, he expands upon the story related in the hour-long film, offering additional historical detail and context to offer a rich, full portrait of this ordinary couple and their extraordinary actions.

Drawing from Eleanor Kraus's unpublished memoir, rare historical documents, and interviews with more than a dozen of the surviving children, and illustrated with period photographs, archival materials, and memorabilia, 50 Children is a remarkable tale of personal courage and triumphant heroism that offers a fresh, unique insight into a critical period of history.

In early 1939, America's rigid immigration laws made it virtually impossible for European Jews to seek safe haven in the United States. As deep-seated anti-Semitism and isolationism gripped much of the country, neither President Roosevelt nor Congress rallied to their aid.

Yet one brave Jewish couple from Philadelphia refused to silently stand by. Risking their own safety, Gilbert Kraus, a successful lawyer, and his stylish wife, Eleanor, traveled to Nazi-controlled Vienna and Berlin to save fifty Jewish children. Steven Pressman brought the Kraus's rescue mission to life in his acclaimed HBO documentary, 50 Children. In this book, he expands upon the story related in the hour-long film, offering additional historical detail and context to offer a rich, full portrait of this ordinary couple and their extraordinary actions.

Drawing from Eleanor Kraus's unpublished memoir, rare historical documents, and interviews with more than a dozen of the surviving children, and illustrated with period photographs, archival materials, and memorabilia, 50 Children is a remarkable tale of personal courage and triumphant heroism that offers a fresh, unique insight into a critical period of history.

Review: I received an uncorrected proof copy of this book from HarperCollins.

50 Children tells the story of an ordinary American couple who, outraged by the events taking place in Europe in 1939, set out to make a difference. Gilbert and Eleanor Krauss managed to safely bring 50 Jewish children from Nazi-occupied Austria to America. Remarkably, although this represents the single largest group of unaccompanied refugee children allowed into the United States, little was known about this story until now. The author had access to Eleanor's personal account of the story since Eleanor and Gilbert are Pressman's wife's maternal grandparents.

After determining to help in some way, Gil discovered in analyzing visa documentation that "the number of visas appeared to exceed the final number of immigrants" actually entering the United States (54). This made no sense, especially in light of the thousands of Jews desperately trying to leave Nazi-occupied countries only to be thwarted by the heavily regulated immigration system in other countries. In other words, although the Nazis were encouraging the Jews to leave, there was no where for them to go. The difference in the number of visas and the number of immigrants was explained by those who had applied to the wait list and later found passage to another country, leaving their visa to the United States unused. Gil sought to use these leftover visas to bring children to America.

The first half of this book dealt largely with the Krauses navigating the complicated paperwork that would allow them to have permission to legally bring the children into the country. This section was relatively slow. Additionally, it seems as if the author had a hard time integrating the children's backgrounds into the story and only gives one disjointed chapter where several of the children's family backgrounds are quickly summarized; it's difficult to get personal simply because of the sheer number of children whose lives were affected by the Krauses mission.

It's obvious how desperate the Austrian parents were if they were willing to send their children away with complete strangers to a foreign land, with the chance that they would never be reunited. Or as Eleanor said, "to take a child from its mother seemed to be the lowest thing a human being could do. Yet it was as if we had drawn up in a lifeboat in a most turbulent sea" (145). The Krauss couple interviewed hundreds of children and made what must have been agonizing decisions about which children would be coming to America. Each parent was anxious that their child would be selected. For example, one mother told her daughter, "If you leave, your life will be saved, and then I will have a better chance of saving my own life" (119). Gil and Eleanor were literally selecting those who would survive. I was particularly moved to read that one child, five-year-old Heinrich Stenberger, who had been selected for the trip later had to be replaced after he fell ill. Tragically, Heinrich "was murdered at the Sobibor death camp three years later" (253).

I was a little disturbed by how much luxury figured into this story. Eleanor and Gil traveled in style and spent time sight seeing and vacationing while abroad to retrieve the children. On the ship home, the children stayed in third class while Eleanor and Gil stayed in first class. On the other hand, I can hardly judge them for this, especially when considering that they are one of only a few Americans who made any attempt to assist Jews in Europe. "In the United States, the most common myth, embraced to explain America's failure to act more compassionately toward refugees and more forcefully in the face of mass murder, is that we did not know what Nazi Germany, her allies and collaborators, were doing. [...] What distinguished [the Krauses] from others is simply that they chose not to close their eyes to what they were reading" (256). They risked their lives to help a large group of children. In fact, while Great Britain took in 10,000 children, the United States took in only about 1,000 - meaning the the Krauses were personally responsible for 1 of every twenty of those children that made it to the United States (258).

Most of the children were placed with relatives or foster families until they were able to be reunited with their parents. Most lived the rest of their lives in the United States. It was amazing to see the accomplishments of many of them, including Henny Wenkart who holds a master's degree from Columbia and a doctorate from Harvard (248). However, Pressman was only able to account for 37 of the children; I'd love to know the fate of the rest of the group.

Stars: 4

Comments

Post a Comment