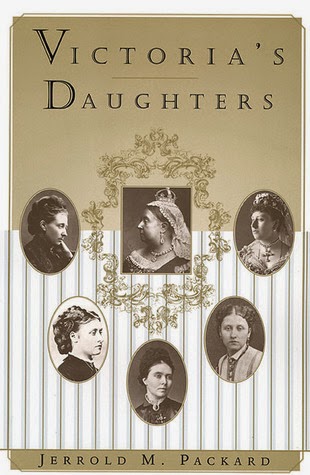

Victoria's Daughters

Summary (from the publisher): Five women who shared one of the most extraordinary and privileged sisterhoods of all time...

Vicky, Alice, Helena, Louise, and Beatrice were historically unique sisters, born to a sovereign who ruled over a quarter of the earth's people and who gave her name to an era: Queen Victoria. Two of these princesses would themselves produce children of immense consequence. All five would face the social restrictions and familial machinations borne by nineteenth-century women of far less exalted class.

Researched at the houses and palaces of its five subjects-- in London, Scotland, Berlin, Darmstadt, and Ottawa-- Victoria's Daughters examines a generation of royal women who were dominated by their mother, married off as much for political advantage as for love, and passed over entirely when their brother Bertie ascended to the throne. Packard, an experienced biographer whose last book chronicled Victoria's final days, provides valuable insights into their complex, oft-tragic lives as scions of Europe's most influential dynasty, and daughters of their own very troubled times.

Review: After thoroughly enjoying We Two, the joint biography of Victoria and her husband Albert by Gillian Gill, I was very curious to learn more about the couple's large family. Although Victoria and Albert had nine children in total, Packard's book focuses on the lives of Queen Victoria's five daughters: Vicky, Alice, Helena (known as Lenchen), Louise, and Beatrice. Although none of her children are as well known today as Queen Victoria herself, they did give her forty grandchildren, whose descendants are scattered throughout almost all the royal families in Europe.

Although Victoria was to become a doting and relaxed grandmother, she was a formal and strict mother. Unfortunately for subsequent children, Victoria and Albert seem to have been dazzled by their firstborn, daughter Vicky, who turned out to be much brighter than the rest of her siblings. Bertie, the heir to Victoria's throne, suffered most greatly from comparison to his sister's intelligence and under the harsh childhood imposed upon him by his parents. This often cruel parenting style was inherited by several of Victoria's children, especially Vicky. I was particularly bothered by the cruel way many of the women spoke about their children in letters to one another. For example, in 1872 Vicky wrote her mother Victoria complaining about her son Henry saying, "Henry is awfully backward in everything, and does not grow - is hopelessly lazy - dull and idle about his lessons - but such a good-natured boy - everybody likes him though he is dreadfully provoking to teach from being so desperately slow" (174).

I was also particularly struck by the agonizing ordeal it was for appropriate marriages to be made for each of Victoria's daughters. It was a complicated decision based on royal rank, wealth, political relationships, religion, and Victoria's own personal desire to keep her daughters as close to her as possible. Vicky made the most brilliant marriage, to Frederick III, the German Emperor. Alice was married to Louis IV, the Grand Duke of Hesse-Darmstadt, Helena to the Prince of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Augustenburg, Louise to the 9th Duke of Argyll, and Beatrice to the Prince of Battenberg. The royal relationships across Europe were frankly difficult for me to follow, complicated by intricate family trees with overlaps where cousins constantly married others.

Most shocking of the marriages was that of Louise, who was the first English Princess to marry a British subject in more than 350 years. "The last time it has happened was in 1515, when Henry VII's youngest daughter married the duke of Suffolk" (132). I was also surprised that Victoria relaxed her strict edict that Beatrice was not to marry, since she expected her younger daughter to remain a spinster in order to remain at home to serve her mother the queen. Victoria graciously relented, although her new son-in-law had to promise to live in Victoria's palace so Beatrice would always be available for the queen, effectively removing any possibility of him having a role to play or work to accomplish throughout his married life. Of course, Victoria only graciously relented after a stand off with Beatrice. "Beatrice still came to the queen's table to eat, but perfect silent was maintained as neither spoke to the other, instead shoving their notes across the table if there was something the other needed to know. This went on for six months" (228) - until Victoria decided maybe Beatrice should be allowed to marry after all.

On the whole, the princesses had cloistered and rigid childhoods and the pinnacle of their lives were their marriages. Of course, some did break out of the mold, Alice to dedicated service work and Louise through pursuing her interest in art. But by far their greatest contribution to history was continuing the royal line of Victoria and scattering her descendants throughout Europe. For instance, Alice's daughter Alix would marry Nicholas II, Tsar of Russia, meaning that the well-known Russian Anastasia was Victoria's great-granddaughter. Additionally, this bloodline meant countless male victims of hemophilia throughout Europe's royal families, passed on by Victoria's daughters, many of whom were carriers of the often fatal blood disorder.

I still would like to know more about Victoria's sons, who were only glossed over in this book. Additionally, at times I found this book a bit difficult to follow, although the large family tree was at the root of this issue. Packard did an excellent job of packing a lot of detail into a relatively small book and providing a thorough overview of Victoria's relationship with her five daughters.

Stars: 4

Vicky, Alice, Helena, Louise, and Beatrice were historically unique sisters, born to a sovereign who ruled over a quarter of the earth's people and who gave her name to an era: Queen Victoria. Two of these princesses would themselves produce children of immense consequence. All five would face the social restrictions and familial machinations borne by nineteenth-century women of far less exalted class.

Researched at the houses and palaces of its five subjects-- in London, Scotland, Berlin, Darmstadt, and Ottawa-- Victoria's Daughters examines a generation of royal women who were dominated by their mother, married off as much for political advantage as for love, and passed over entirely when their brother Bertie ascended to the throne. Packard, an experienced biographer whose last book chronicled Victoria's final days, provides valuable insights into their complex, oft-tragic lives as scions of Europe's most influential dynasty, and daughters of their own very troubled times.

Review: After thoroughly enjoying We Two, the joint biography of Victoria and her husband Albert by Gillian Gill, I was very curious to learn more about the couple's large family. Although Victoria and Albert had nine children in total, Packard's book focuses on the lives of Queen Victoria's five daughters: Vicky, Alice, Helena (known as Lenchen), Louise, and Beatrice. Although none of her children are as well known today as Queen Victoria herself, they did give her forty grandchildren, whose descendants are scattered throughout almost all the royal families in Europe.

Although Victoria was to become a doting and relaxed grandmother, she was a formal and strict mother. Unfortunately for subsequent children, Victoria and Albert seem to have been dazzled by their firstborn, daughter Vicky, who turned out to be much brighter than the rest of her siblings. Bertie, the heir to Victoria's throne, suffered most greatly from comparison to his sister's intelligence and under the harsh childhood imposed upon him by his parents. This often cruel parenting style was inherited by several of Victoria's children, especially Vicky. I was particularly bothered by the cruel way many of the women spoke about their children in letters to one another. For example, in 1872 Vicky wrote her mother Victoria complaining about her son Henry saying, "Henry is awfully backward in everything, and does not grow - is hopelessly lazy - dull and idle about his lessons - but such a good-natured boy - everybody likes him though he is dreadfully provoking to teach from being so desperately slow" (174).

I was also particularly struck by the agonizing ordeal it was for appropriate marriages to be made for each of Victoria's daughters. It was a complicated decision based on royal rank, wealth, political relationships, religion, and Victoria's own personal desire to keep her daughters as close to her as possible. Vicky made the most brilliant marriage, to Frederick III, the German Emperor. Alice was married to Louis IV, the Grand Duke of Hesse-Darmstadt, Helena to the Prince of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Augustenburg, Louise to the 9th Duke of Argyll, and Beatrice to the Prince of Battenberg. The royal relationships across Europe were frankly difficult for me to follow, complicated by intricate family trees with overlaps where cousins constantly married others.

Most shocking of the marriages was that of Louise, who was the first English Princess to marry a British subject in more than 350 years. "The last time it has happened was in 1515, when Henry VII's youngest daughter married the duke of Suffolk" (132). I was also surprised that Victoria relaxed her strict edict that Beatrice was not to marry, since she expected her younger daughter to remain a spinster in order to remain at home to serve her mother the queen. Victoria graciously relented, although her new son-in-law had to promise to live in Victoria's palace so Beatrice would always be available for the queen, effectively removing any possibility of him having a role to play or work to accomplish throughout his married life. Of course, Victoria only graciously relented after a stand off with Beatrice. "Beatrice still came to the queen's table to eat, but perfect silent was maintained as neither spoke to the other, instead shoving their notes across the table if there was something the other needed to know. This went on for six months" (228) - until Victoria decided maybe Beatrice should be allowed to marry after all.

On the whole, the princesses had cloistered and rigid childhoods and the pinnacle of their lives were their marriages. Of course, some did break out of the mold, Alice to dedicated service work and Louise through pursuing her interest in art. But by far their greatest contribution to history was continuing the royal line of Victoria and scattering her descendants throughout Europe. For instance, Alice's daughter Alix would marry Nicholas II, Tsar of Russia, meaning that the well-known Russian Anastasia was Victoria's great-granddaughter. Additionally, this bloodline meant countless male victims of hemophilia throughout Europe's royal families, passed on by Victoria's daughters, many of whom were carriers of the often fatal blood disorder.

I still would like to know more about Victoria's sons, who were only glossed over in this book. Additionally, at times I found this book a bit difficult to follow, although the large family tree was at the root of this issue. Packard did an excellent job of packing a lot of detail into a relatively small book and providing a thorough overview of Victoria's relationship with her five daughters.

Stars: 4

Comments

Post a Comment