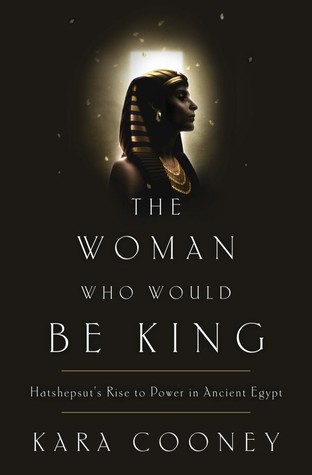

The Woman Who Would Be King: Hatshepsut's Rise to Power in Ancient Egypt

Summary (from the publisher): An engrossing biography of the longest-reigning female pharaoh in Ancient Egypt and the story of her audacious rise to power in a man’s world.

Hatshepsut, the daughter of a general who took Egypt's throne without status as a king’s son and a mother with ties to the previous dynasty, was born into a privileged position of the royal household. Married to her brother, she was expected to bear the sons who would legitimize the reign of her father’s family. Her failure to produce a male heir was ultimately the twist of fate that paved the way for her inconceivable rule as a cross-dressing king. At just twenty, Hatshepsut ascended to the rank of king in an elaborate coronation ceremony that set the tone for her spectacular twenty-two year reign as co-regent with Thutmose III, the infant king whose mother Hatshepsut out-maneuvered for a seat on the throne. Hatshepsut was a master strategist, cloaking her political power plays with the veil of piety and sexual expression. Just as women today face obstacles from a society that equates authority with masculinity, Hatshepsut had to shrewdly operate the levers of a patriarchal system to emerge as Egypt's second female pharaoh.

Hatshepsut had successfully negotiated a path from the royal nursery to the very pinnacle of authority, and her reign saw one of Ancient Egypt’s most prolific building periods. Scholars have long speculated as to why her images were destroyed within a few decades of her death, all but erasing evidence of her rule. Constructing a rich narrative history using the artifacts that remain, noted Egyptologist Kara Cooney offers a remarkable interpretation of how Hatshepsut rapidly but methodically consolidated power—and why she fell from public favor just as quickly. The Woman Who Would Be King traces the unconventional life of an almost-forgotten pharaoh and explores our complicated reactions to women in power.

Hatshepsut, the daughter of a general who took Egypt's throne without status as a king’s son and a mother with ties to the previous dynasty, was born into a privileged position of the royal household. Married to her brother, she was expected to bear the sons who would legitimize the reign of her father’s family. Her failure to produce a male heir was ultimately the twist of fate that paved the way for her inconceivable rule as a cross-dressing king. At just twenty, Hatshepsut ascended to the rank of king in an elaborate coronation ceremony that set the tone for her spectacular twenty-two year reign as co-regent with Thutmose III, the infant king whose mother Hatshepsut out-maneuvered for a seat on the throne. Hatshepsut was a master strategist, cloaking her political power plays with the veil of piety and sexual expression. Just as women today face obstacles from a society that equates authority with masculinity, Hatshepsut had to shrewdly operate the levers of a patriarchal system to emerge as Egypt's second female pharaoh.

Hatshepsut had successfully negotiated a path from the royal nursery to the very pinnacle of authority, and her reign saw one of Ancient Egypt’s most prolific building periods. Scholars have long speculated as to why her images were destroyed within a few decades of her death, all but erasing evidence of her rule. Constructing a rich narrative history using the artifacts that remain, noted Egyptologist Kara Cooney offers a remarkable interpretation of how Hatshepsut rapidly but methodically consolidated power—and why she fell from public favor just as quickly. The Woman Who Would Be King traces the unconventional life of an almost-forgotten pharaoh and explores our complicated reactions to women in power.

Review: I won an uncorrected proof copy as a giveaway on Goodreads.

For years, historians have "disparaged her character, saying little about her success and a great deal about how she had stolen the throne from its rightful heir, Thutmose III" (232). In this biography, Cooney shows that Hatshepsut, the famous female king of ancient Egypt, may have been more than long has been imagined.

Hatsheptsut was born around 1500 BCE, the daughter of King Thutmose I. Her father was the first in his dynasty after the previous king, Amenhotep I, died childless. As the king's daughter with his Great Wife, Hatsheptsut was raised to expect that she would one day marry her brother, who would become King Thutmose II. The most suitable mate for the king was the woman with the most royal bloodline - his sister. Hatshepsut was both king's daughter, king's sister, and king's wife. Her bloodline was impeccable.

However, Hatshepsut's brother and husband Thutmose II appears to never have been a healthy man. "His skin was covered with lesions and raised pustules. He had an enlarged heart, which meant he probably suffered with arrhythmias and shortness of breath" (53). He died before Hatshepsut produced a son to continue the dynasty. Instead, a young son of Thutmose II and a non-noble woman from his harem was selected to become Thutmose III. Although it was not unusual for mothers to act as regents for young sons, it was unusual for an aunt to act as regent. "In many ways, Thutmose III ruled as king only because Hatshepsut was there to make it happen. He only took the throne because she had been able to keep all other contenders and threats to her dead husband's child at bay" (77).

Cooney posits that the answer to maintaining stability of the kingdom was to transition her regency to a co-kingship. The author argues that, although unorthodox, Hatshepsut's move to crown herself king alongside her young nephew was a brilliant move to maintain power that might have been lost by the very young king. Although her move seems like a bid for power, the powerful men throughout the kingdom seem to have allowed and supported this move; "these men were apparently so troubled by Thutmose III's immature kingship that they were ready to support the most unorthodox political move possible to keep her in power" (110).

Nearly twenty years after her death, Thutmose III began destroying all the visible stone carvings and monuments that referred to his aunt and co-regent. Previous historians argue that this is a sign of how Thutmose III tried to destroy the image of an abhorrent, power-hungry woman. However, Cooney points out that at the beginning of his reign, "he had actually ordered his craftsman to finish her monuments and piously added his name and likeness to Hatshepsut's sacred structures" (215). Only twenty years later did he decide to destroy them, perhaps because he feared for his own son's future rule. Eliminating the image of a royal takeover of power, or what was perceived as such, might strengthen his own young son's claim to the throne as sole regent.

The last time I spent much time with Egyptian history was when I took ancient history in middle school. I'm unfamiliar with many aspects of this time period. In particular, I was unaware of the immense religious rituals that were involved in the kingship. I also found the overview of the many horrendous health issues of the time interesting. Nearly everyone suffered from worms, nearly all contracted smallpox, and all food had "a tiny dose of quartz dust that wore down tooth enamel, until the dentin was compromised and infection could easily eat away the root of a tooth. Abscesses followed, tunneling deep into the bone of the jaw, forming hollows full of pus that would eventually burst, spreading poison throughout the bloodstream. Infected teeth killed kings as readily as commoners" (43). Most Egyptians did well to make it to age 30.

Cooney is writing about a time period and a woman that is heavily obscured by history, and the fact that Egyptians neatly omitted gossip from written accounts. However, given the many uncertainties, she has painted a portrait of a woman who has been maligned for centuries. "Hatshepsut has the misfortune to be antiquity's female leader who did everything right, a woman who could match her wit and energy to a task so seamlessly that she made no waves of discontent that have been recorded" (2). Although we'll never know many details of Hatshepsut's life or choices, Cooney has gleaned extraordinary insight from the facts left to us.

Stars: 4

Comments

Post a Comment