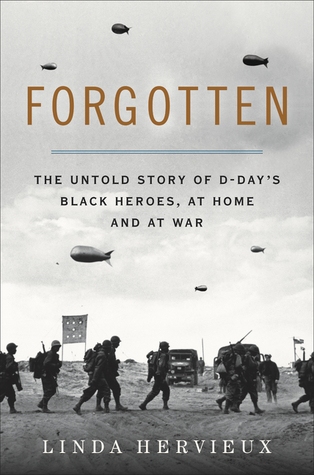

Forgotten: The Untold Story of D-Day's Black Heroes, at Home and at War

Summary (from the publisher): The injustices of 1940s Jim Crow America are brought to life in this extraordinary blend of military and social history—a story that pays tribute to the valor of an all-black battalion whose crucial contributions at D-Day have gone unrecognized to this day.

In the early hours of June 6, 1944, the 320th Barrage Balloon Battalion, a unit of African-American soldiers, landed on the beaches of France. Their orders were to man a curtain of armed balloons meant to deter enemy aircraft. One member of the 320th would be nominated for the Medal of Honor, an award he would never receive. The nation’s highest decoration was not given to black soldiers in World War II.

Drawing on newly uncovered military records and dozens of original interviews with surviving members of the 320th and their families, Linda Hervieux tells the story of these heroic men charged with an extraordinary mission, whose contributions to one of the most celebrated events in modern history have been overlooked. Members of the 320th—Wilson Monk, a jack-of-all-trades from Atlantic City; Henry Parham, the son of sharecroppers from rural Virginia; William Dabney, an eager 17-year-old from Roanoke, Virginia; Samuel Mattison, a charming romantic from Columbus, Ohio—and thousands of other African Americans were sent abroad to fight for liberties denied them at home. In England and Europe, these soldiers discovered freedom they had not known in a homeland that treated them as second-class citizens—experiences they carried back to America, fueling the budding civil rights movement.

In telling the story of the 320th Barrage Balloon Battalion, Hervieux offers a vivid account of the tension between racial politics and national service in wartime America, and a moving narrative of human bravery and perseverance in the face of injustice.

In the early hours of June 6, 1944, the 320th Barrage Balloon Battalion, a unit of African-American soldiers, landed on the beaches of France. Their orders were to man a curtain of armed balloons meant to deter enemy aircraft. One member of the 320th would be nominated for the Medal of Honor, an award he would never receive. The nation’s highest decoration was not given to black soldiers in World War II.

Drawing on newly uncovered military records and dozens of original interviews with surviving members of the 320th and their families, Linda Hervieux tells the story of these heroic men charged with an extraordinary mission, whose contributions to one of the most celebrated events in modern history have been overlooked. Members of the 320th—Wilson Monk, a jack-of-all-trades from Atlantic City; Henry Parham, the son of sharecroppers from rural Virginia; William Dabney, an eager 17-year-old from Roanoke, Virginia; Samuel Mattison, a charming romantic from Columbus, Ohio—and thousands of other African Americans were sent abroad to fight for liberties denied them at home. In England and Europe, these soldiers discovered freedom they had not known in a homeland that treated them as second-class citizens—experiences they carried back to America, fueling the budding civil rights movement.

In telling the story of the 320th Barrage Balloon Battalion, Hervieux offers a vivid account of the tension between racial politics and national service in wartime America, and a moving narrative of human bravery and perseverance in the face of injustice.

Review: I received an uncorrected proof copy of this book from HarperCollins.

Linda Hervieux has managed to shed light on a group of American heroes that sadly truly were nearly forgotten in this new work of non-fiction. In it, the author tells the story of the 320th Barrage Balloon Battalion, a unit of African American soldiers, who assisted in deterring enemy aircraft on the beaches of France. Despite their heroic actions, most of these men were never awarded medals, are never represented even in fictional portrayals of D-Day, and returned home to a country that promptly regulated them to basically second class citizenship due to their race - many even struggled to be given the benefits supposedly open to them through the GI bill.

Hervieux did an excellent job of not only describing these men's war efforts, but setting the scene to show it was remarkable that they were even given the responsibility of the barrage balloons. At the time, in the 1940s, most black men in the armed forces were relegated to menial tasks. In 1925, the Army released a study that helps depict how African American soldiers were viewed: "He has not the physical courage of the white. He simply cannot control himself in fear of some danger in the degree that the white man can. His psychology is such that he willingly accepts hard labor and for this reason can be well employed in labor troops or other non-combatant branches" (27). Although somewhat welcomed in the army, black were excluded from the marines, only allowed to work as servants in the navy, and completely excluded form the Army Air Corps, the forerunner to the air force (39).

The 320th were trained at Camp Tyson in Tennessee, where many of these northern men faced Jim Crow racism of the South for the first time. German prisoners of war were welcomed into restaurants where blacks were excluded. The very sight of African American men in uniform and standing at attention - "a pose of strength, dignity and pride" - was deeply offensive to white southerners. Yet when they arrived in Britain, the men were astounded to be treated as equal with whites for the first time - they were invited to British home for dinner and were welcomed in British restaurants, pubs, and churches - here they "were Americans first" (158). This caused racial tensions between white and black American soldiers to escalate, contributing to anxiety from British officials, who resented Americans importing their racial issues to Britain. In fact, the polite demeanor and general appreciation for equal treatment led their hosts to say, "the general consensus of opinion seems to be that the only American soldiers with decent manners are the Negroes" (155).

In addition to shedding light on men worthy of our recognition and respect, I enjoyed learning about the use of barrage balloons, which I had never studied in detail before. Hervieux reports that she had difficulty finding information on wartime balloons "because there are so few people alive today who know anything about them" (271). Apparently the first balloon was used in a military sense by Napoleon in 1794. Balloons were used in the second world war to effectively keep planes away from a target. "As a defensive barrier, a curtain of balloons flying in a staggered sawtooth pattern forced pilots higher, fouling the aim of their bombs. Flying higher also made those planes better targets for the big guns on the ground" (67). Early balloons were also filled with hydrogen, which would explode when a plane collided with it and their cables held bombs that were triggered when planes came in contact with them.

Hervieux embarked on this research in the nick of time - only a few men from the 320th were still alive when she began locating them. I feel grateful that she was able to interview some of the men and finally shed light on their contributions to ending World War II - like Waverly Woodson, who worked thirty hours straight as a medic on the beaches of Omaha before collapsing. When he woke up, he asked to go back to keep helping.

At times I did feel like this book was merely plumbing the surface of the 320th's stories. I would love to have had more accounts of the individual men, although this was likely complicated by many having passed away by the time of writing. However, overall this was an excellent read about a sorely undocumented part of our history.

Stars: 4

Comments

Post a Comment